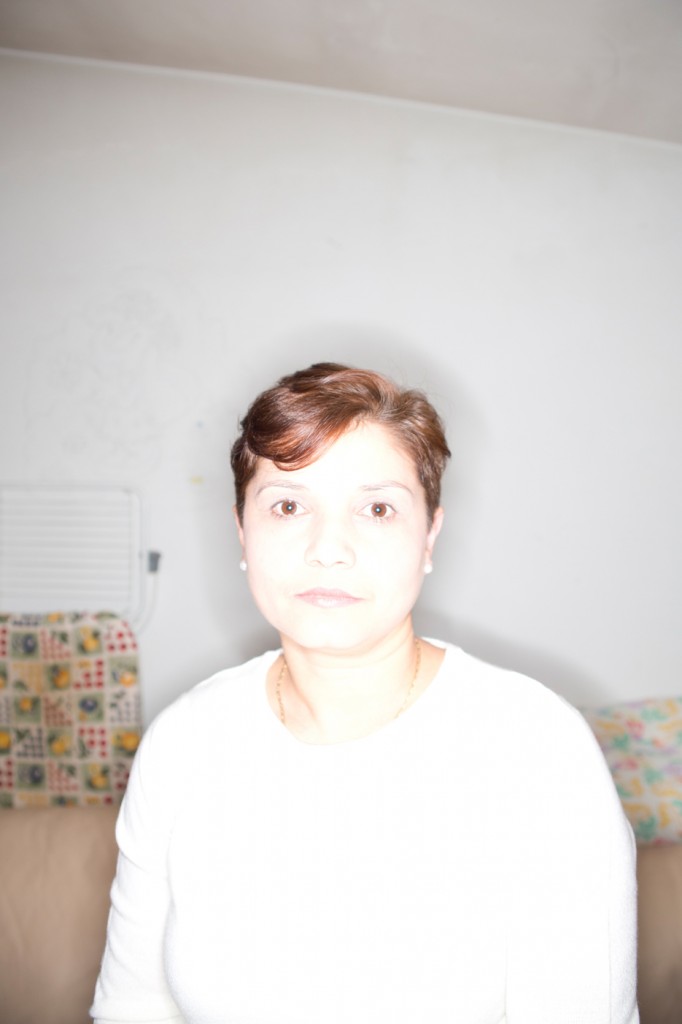

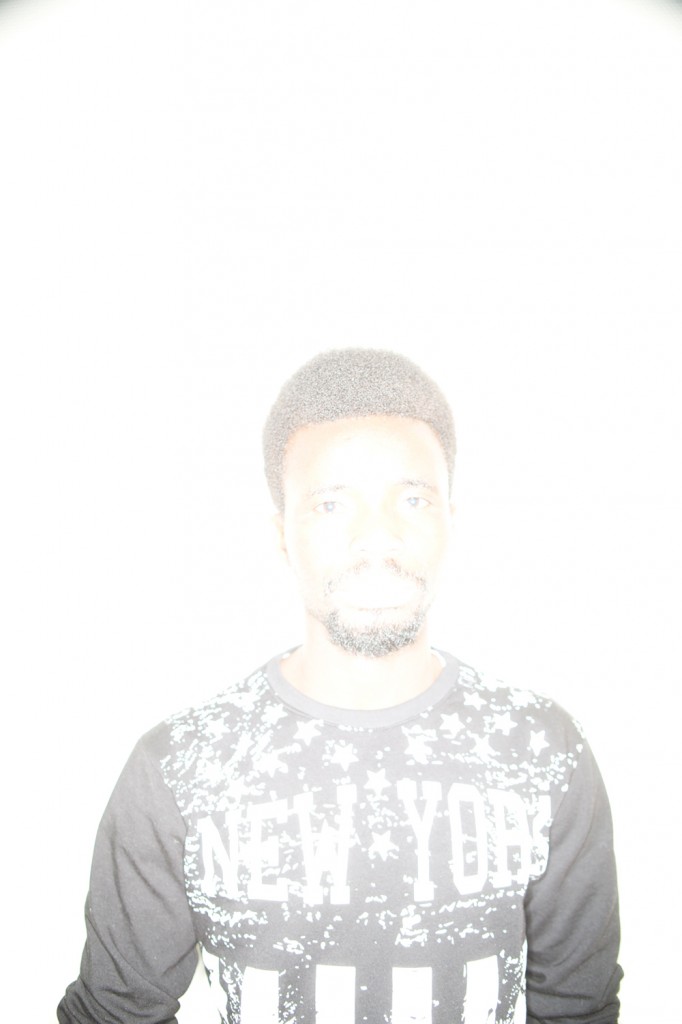

A million, or maybe two. It is not known precisely. But among regular contracts and jobs in black, more or less that is the amount that can be reached. They are domestic workers, caregivers, baby-sitters, nannies or how you want them to call. Arriving in Italy from countries in economic difficulty, particularly from Eastern Europe and the Philippines, but also from Latin America or Africa. They all leave for the same reasons. To escape destitution, to support the family, to give a future to the children. These same children who, in most cases, they leave behind them, trusting them to grandparents and close relatives and suffers in silence and lack, hoping every day to find a way to be joined. These same children who will grow up trying to find a balance between a sense of abandonment, anger, blame themselves and at the same time aware of the parents’ sacrifice. In some extreme cases, those children will kill themselves. This particular migration phenomenon affects mainly women, because it is easier for them to find this type of jobs. Each one is different, but all share the same history. They decide to leave convinced of some friend or relative who has already taken the same path and can help them find employment. They plan to stay a few months, a year at most, just enough time to recover economically and to put together enough money to buy a house. But the months turn into years and the return becomes increasingly difficult. The new wellness reserved to families, and hardly won, gets the better of fatigue and discontent and the return is postponed indefinitely. Many are lucky and find “good” employers, which provide them with all the contractual rights and treat them with warmth and respect. In many, however, are having to face untenable situations: they work in black and underpaid, are harassed and discriminated, holidays are not recognize and payable days off not granted (often half-days), and so on. These departures have a strong impact and significant consequences both in the family and on society as a whole. Changing relationships between parents and children, husbands and wives, change roles, fathers are often home to take care of children. Women are emancipated, leaving the country by themselves, often for the first time in their lives. They find themselves in places that do not know, where people speak languages they do not understand and lifestyles and have cultural models that they do not share. The shock is high and produces even inner changes. Changes in outlook on life, changes in perspectives, changes in habits. They will lose friendships, have to find a way to survive the remote and the sacrifice. Expectations and dreams soon fade away. It all comes down to the everyday life of a totalizing and exhausting job. They come home, if all goes well, once a year and at that poor month, commit themselves totally and try to recover the relationship with their children, because the physical distance erodes confidence. They face prejudice, not only in the country in which they arrive, implicated as those that are “doing the good life”, but also at home because guilty to leave their families and children in particular. This exodus affects all social classes, knows no distinction between educational qualifications, work experience, age. Desperation is the common denominator. The lack of alternatives, the inability to take action on the biggest factors of themself, the misfortune of being in certain conditions, not by their own choice or fault. Because, at the end, it is always a matter of luck. The differences between human beings are just a matter of luck. It all depends on where you are born, the historical moment in which you live, what you have or do not have. And when you have nothing, everything becomes a luxury. Luck, too.

A million, or maybe two. It is not known precisely. But among regular contracts and jobs in black, more or less that is the amount that can be reached. They are domestic workers, caregivers, baby-sitters, nannies or how you want them to call. Arriving in Italy from countries in economic difficulty, particularly from Eastern Europe and the Philippines, but also from Latin America or Africa. They all leave for the same reasons. To escape destitution, to support the family, to give a future to the children. These same children who, in most cases, they leave behind them, trusting them to grandparents and close relatives and suffers in silence and lack, hoping every day to find a way to be joined. These same children who will grow up trying to find a balance between a sense of abandonment, anger, blame themselves and at the same time aware of the parents’ sacrifice. In some extreme cases, those children will kill themselves. This particular migration phenomenon affects mainly women, because it is easier for them to find this type of jobs. Each one is different, but all share the same history. They decide to leave convinced of some friend or relative who has already taken the same path and can help them find employment. They plan to stay a few months, a year at most, just enough time to recover economically and to put together enough money to buy a house. But the months turn into years and the return becomes increasingly difficult. The new wellness reserved to families, and hardly won, gets the better of fatigue and discontent and the return is postponed indefinitely. Many are lucky and find “good” employers, which provide them with all the contractual rights and treat them with warmth and respect. In many, however, are having to face untenable situations: they work in black and underpaid, are harassed and discriminated, holidays are not recognize and payable days off not granted (often half-days), and so on. These departures have a strong impact and significant consequences both in the family and on society as a whole. Changing relationships between parents and children, husbands and wives, change roles, fathers are often home to take care of children. Women are emancipated, leaving the country by themselves, often for the first time in their lives. They find themselves in places that do not know, where people speak languages they do not understand and lifestyles and have cultural models that they do not share. The shock is high and produces even inner changes. Changes in outlook on life, changes in perspectives, changes in habits. They will lose friendships, have to find a way to survive the remote and the sacrifice. Expectations and dreams soon fade away. It all comes down to the everyday life of a totalizing and exhausting job. They come home, if all goes well, once a year and at that poor month, commit themselves totally and try to recover the relationship with their children, because the physical distance erodes confidence. They face prejudice, not only in the country in which they arrive, implicated as those that are “doing the good life”, but also at home because guilty to leave their families and children in particular. This exodus affects all social classes, knows no distinction between educational qualifications, work experience, age. Desperation is the common denominator. The lack of alternatives, the inability to take action on the biggest factors of themself, the misfortune of being in certain conditions, not by their own choice or fault. Because, at the end, it is always a matter of luck. The differences between human beings are just a matter of luck. It all depends on where you are born, the historical moment in which you live, what you have or do not have. And when you have nothing, everything becomes a luxury. Luck, too.